by Jack Elbaum, Sept. 2, 2023- If you thought charter schools received anywhere near the same amount of funding as traditional public schools, then think again.

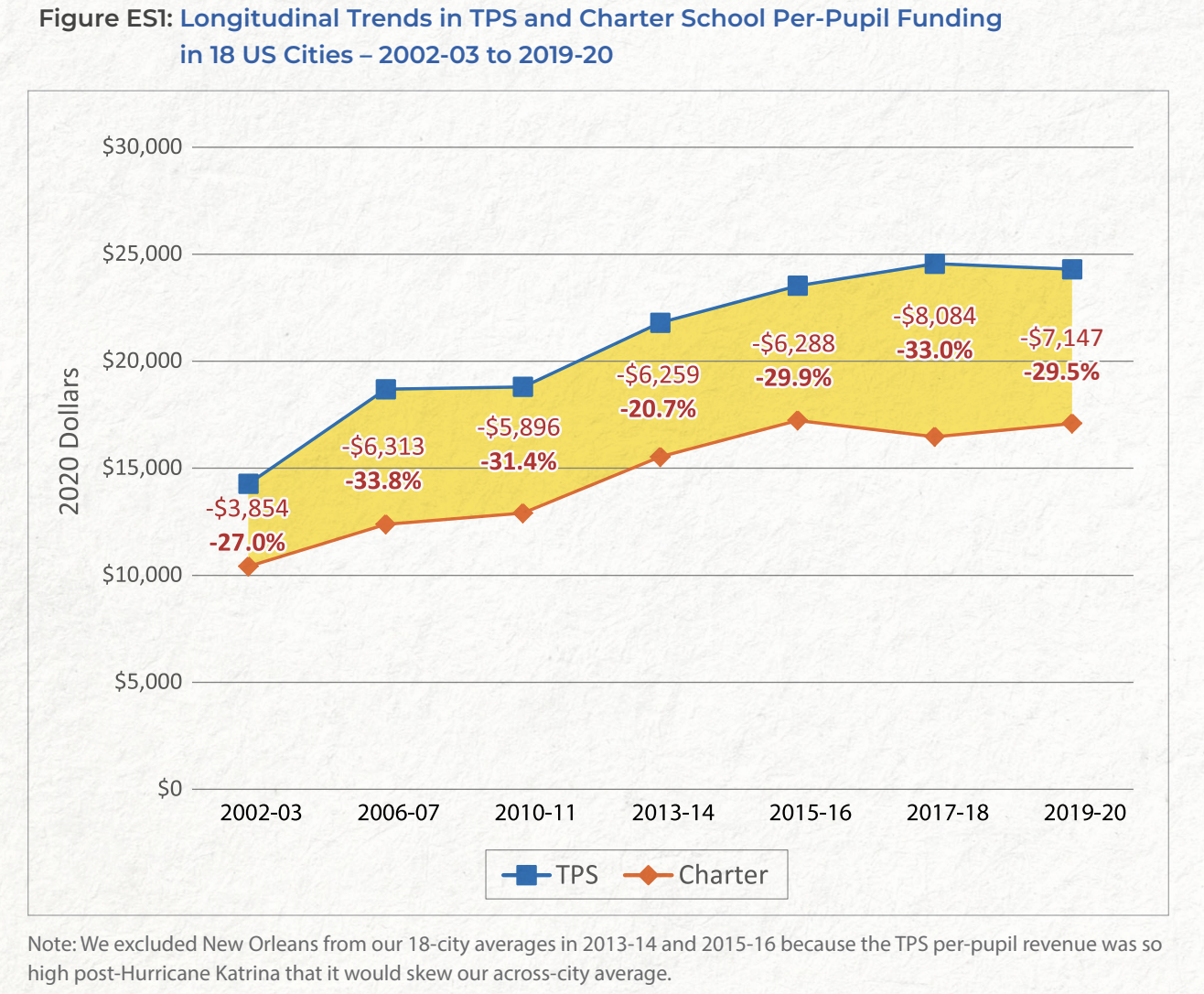

A new, massive study from the University of Arkansas finds that “On average, charter schools across 18 cities in 16 states (...) receive about 30 percent or $7,147 (2020 dollars) less funding per pupil than traditional public schools.” Over the past two decades, this funding disparity has remained relatively stable.

The gaps are, predictably, more severe in some places than others. The study notes that “Atlanta has the largest percentage-based charter funding disparity (about 53 percent), while Camden has the largest disparity in dollars ($19,711). Houston has the smallest disparity in terms of percent (three percent) and dollars ($417).”

Importantly, the regression analysis run by the authors did not suggest differences in the proportion of students in poverty or English Language Learners are the reason for the disparity. However, it did find that after taking into account differences in the number of special needs students, the disparity dropped considerably—although it remained significant ($1,707).

Charters Do Better Anyway

Based on these data alone, it would not be unreasonable for one to expect that these charter schools had worse educational outcomes than their traditional public school counterparts.

The only issue is that this is not the case.

A recent study from Stanford University, for example, found that charter school students gain 16 days' worth of reading and six days of math per year relative to those in traditional public schools. These benefits were particularly pronounced among minority students who were also in poverty. Education Week reported that “Black charter students in poverty gained 37 days of learning in reading and 36 days in math over their counterparts in traditional public schools, and Hispanic students in poverty gained 36 days of reading and 30 days of math over their traditional public school peers.”

Economist Thomas Sowell’s 2020 book Charter Schools and Their Enemies also offers compelling data suggesting the efficacy of charter schools. He studied a set of charters and traditional public schools in New York City that served essentially identical populations. In many cases in the study, a charter school and traditional public school would even occupy the same building.

Nevertheless, the educational outcomes could not be more different. He found that only 10% of the traditional public schools had a majority of students passing at the “proficient” level on the mathematics exam, while 68% of charter schools did. Similarly, on the English exam, only 14% of the traditional public schools had a majority of students pass at the “proficient” level whereas the proportion was 65% for charter schools.

Funding Is Not What Determines Outcomes

This leaves us with a key insight: Funding is not what drives educational outcomes. Yes, it has become clear through considering the superior results of charter schools despite their relatively lower funding. But it is not the only reason we know this.

A 1997 literature review of over 400 studies found that “there is not a strong or consistent relationship between student performance and school resources.” Recent data also reveal that even though inflation-adjusted per-pupil education spending has risen by 245% since 1970, reading scores have risen by less than 1% and math scores have risen by 1.8%.

Additionally, some of the worst school districts in the country are also the best funded. Baltimore City Schools spends more than $21,000 per student and Chicago Public Schools spend almost $30,000 per student. Yet, those districts have at least a dozen schools each where not a single student is proficient in either math or reading.

Meanwhile, Nicholas Kristof at the New York Times recently documented an unprecedented improvement in Mississippi K-12 schools. Fourth graders in Mississippi moved from the bottom of the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) rankings to the middle and the state moved to the top when it came to kids coming from families in poverty. But, importantly, these results did not come as a result of increasing funding. In fact, Mississippi ranks 46th in spending per pupil.

Instead, as I noted in the Washington Examiner, “For an education system to flourish, it needs to stick to the fundamentals. Teaching reading well and setting high expectations go a long way. There is of course so much more schools are doing in order to excel, but much of it comes back to this basic idea.”

This is how Mississippi made its progress, it is how charter networks such as Success Academy flourish, and it is also just common sense. After all, a school can have all the resources in the world, but if it does not teach reading properly or actually hold students to high standards, then there is no reason to believe it will be successful.

Likely the defining difference between charters and traditional public schools, though, is the incentives associated with them. It is hard to overstate how far-reaching the consequences of this are.

In an interview for Charter Schools and Their Enemies, Sowell points out that education is treated wholly different than almost any other industry. Whereas a grocery store or summer camp can only continue to survive if they convince enough people that it is worth spending money there, traditional public schools have to convince nobody. The government simply forces a select group of people, based on their zip code, to attend one school or another. Consequently, whether that school is failing or succeeding, nothing changes as it pertains to attendance, and therefore its ability to continue operating. This is resolutely not the case with charter schools, which can only survive to the extent people actually want to attend them.

This sets up a situation where traditional public schools have no incentive to improve while charter schools must as a matter of survival. It should be no surprise, then, that the latter outperforms the former.

So how can we improve education outcomes?. The answer is to focus on the incentives. An education system built on choice and competition will reward effective schools and weed out ineffective ones. On the other hand, a system built on coercion and monopoly—like the current public school system—is a recipe for perpetual mediocrity.

Jack Elbaum was a Hazlitt Writing Fellow at FEE and is a junior at George Washington University. His writing has been featured in The Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, The New York Post, and the Washington Examiner. You can contact him at jackelbaum16@gmail.com and follow him on Twitter @Jack_Elbaum.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

Top Stories

.png)